Copyright & Fair Use

Welcome to the....

How do works arrive in the Public Domain?

There are five common ways that an item will arrive in the Public Domain.

The copyright has expired.

Copyright has expired for all works made in the United States prior to 1926. If the publication date is before January 1, 1926, then the work is in the Public Domain.

For works published after 1977, copyright will not expire until 70 years after the last surviving author dies.

The Copyright failed to affix the required notice.

Works published in the United States before 1978 immediately entered the public domain if they were generally published without a proper copyright notice. Which required the copyright symbol © (for phonorecords, the symbol ℗) word copyright of the abbreviation copr. along with the name of the holder and the date of first publication. © 1959 John Doe.

Between 1979 and 1989 works published in the United States would entered the public domain if a registration was made within 5 years of initial publication with the Copyright Office and reasonable effort was made to correct the omission on all copies distributed in the U.S. after the omission is discovered.

The copyright owner failed to follow renewal rules.

Works published in the United States before 1964 fall into the public domain if copyright was not renewed with the Copyright Office during the 28th year after publication. No renewal meant a loss of copyright.

For works published between 1925 and 1964, research with the Copyright Office is needed to know whether the item is in the Public Domain. For a helpful guide to researching Copyright Office records, please see this guide from Stanford University Libraries.

The copyright owner deliberately places the item in the Public Domain.

Sometimes, a copyright owner will choose to release their work to the Public Domain. They can do this via a CC-0 license or by placing a statement such as "This work is dedicated to the Public Domain" on their work.

It is important to verify that the person dedicating the work to the Public Domain is, in fact, the owner of the copyright for the work.

Copyright law does not protect this kind of work.

Copyright law does not protect the titles of books or movies, nor does it protect short phrases such as, “Beam me up.”

Copyright protection also doesn’t cover facts, ideas, or theories, which has important ramifications for the collection of data. While the facts of data are not subject to copyright, their organization may be.

(Information for this section pulled from the "Copyright and Intellectual Property Toolkit" from the University of Pittsburgh Libraries.)

Copyright Concepts

Goals of Copyright: The stated goal of US copyright law is to promote progress by securing time-limited exclusive rights for creators. (paraphrased from Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8 of the US Constitution)

Exclusive Rights of Creators: Right now, in the USA, Copyright is automatic for content in a fixed form. If you write a book or draw a picture, those things are under copyright, and you are entitled to six exclusive rights about them:

- The right to reproduce

- The right to create derivative works (eg: adapting a book into a play)

- The right to distribute copies, or transfer ownership of the work

- The right to perform the work publicly

- The right to display the work publicly

- The right to perform the work publicly via digital audio transmission (if sound recording)

You are not required to register your copyright with the Copyright Office. You are not required to include a copyright statement. If you anticipate that your work will be a high-value project, or that there may be a copyright dispute in the future, you can register with the Copyright Office.

There are limitations on these exclusive rights, the most common of which are Fair Use and Reproduction by Libraries and Archives (for an exhaustive list, see: US Code, Title 17, Chapter 1, Section 107-112.

Things that cannot be copyrighted: Facts cannot be copyrighted, which means that things like basic math, recipes, alphabets, grammatical tropes (eg: “I before e, except after c”) and recipes (the list of ingredients and steps themselves) cannot be copyrighted.

On the other side, ideas cannot be copyrighted either. Only creative media in a fixed form is eligible for copyright.

"Copyright Services: Copyright 101" Cornell University LIbrary

Fair Use Checklist

Just because an item is covered by copyright law does not mean that you are unable to use it. The guiding principles of Fair Use asks users to consider four factors when determining their use of a copyrighted work.

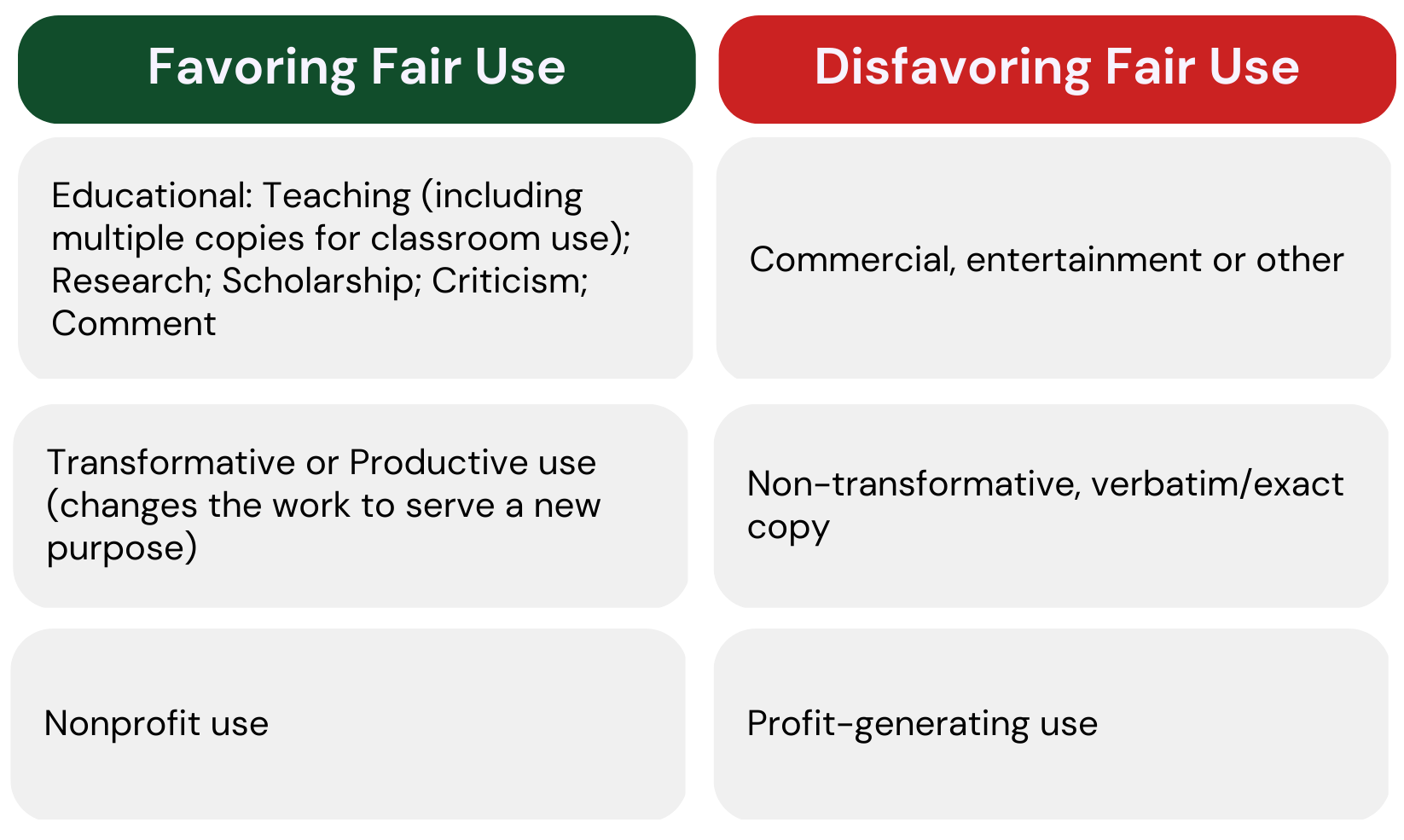

Purpose of the Use

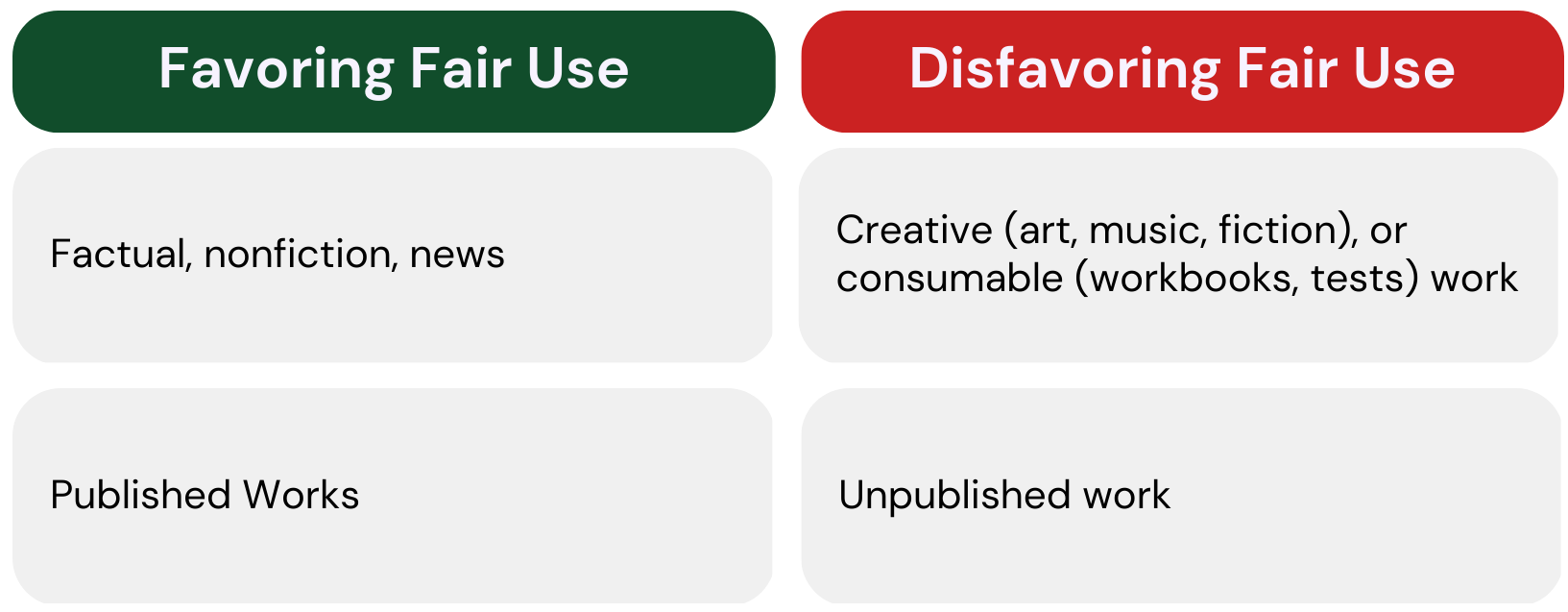

Nature of Copyrighted Material

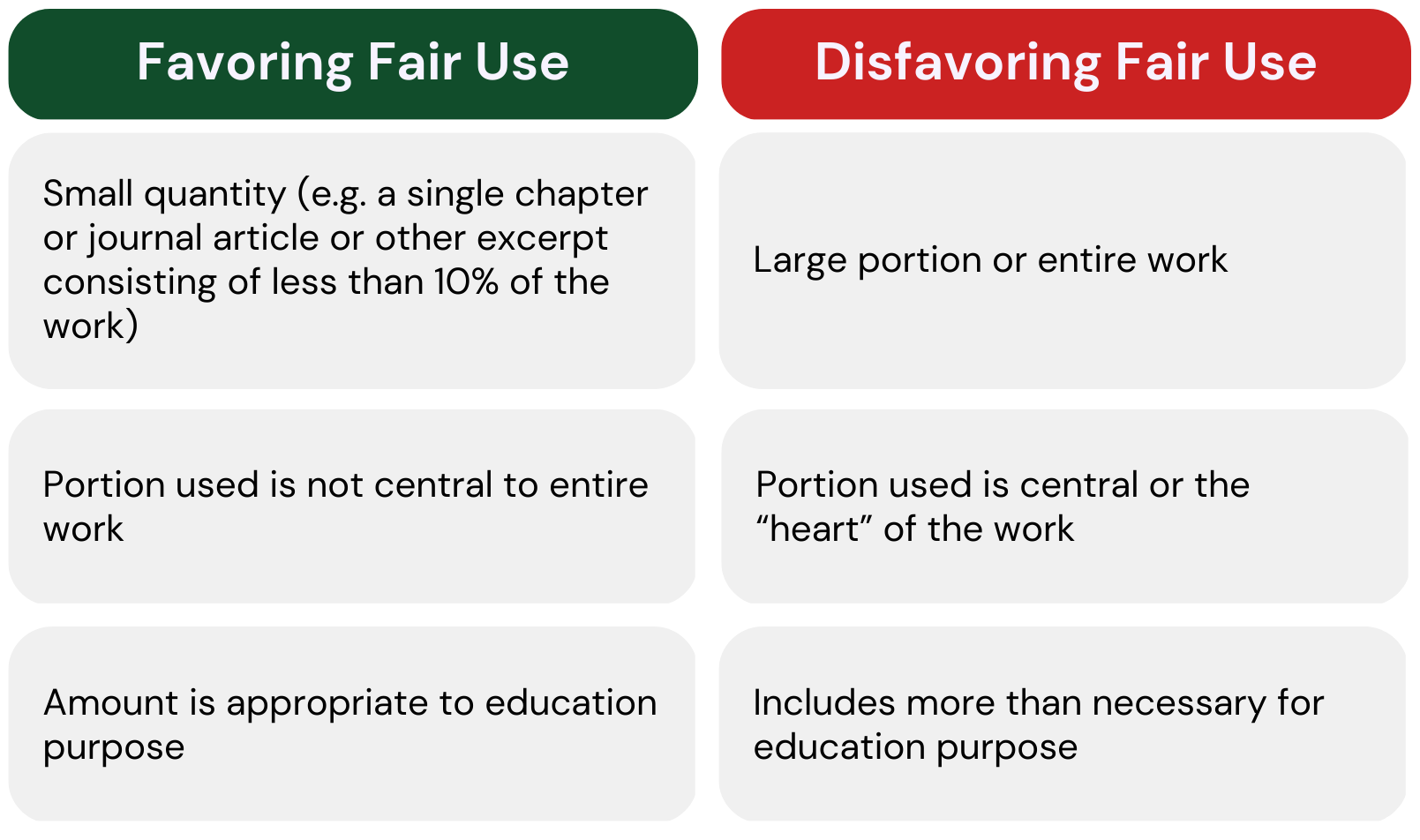

Amount Copied

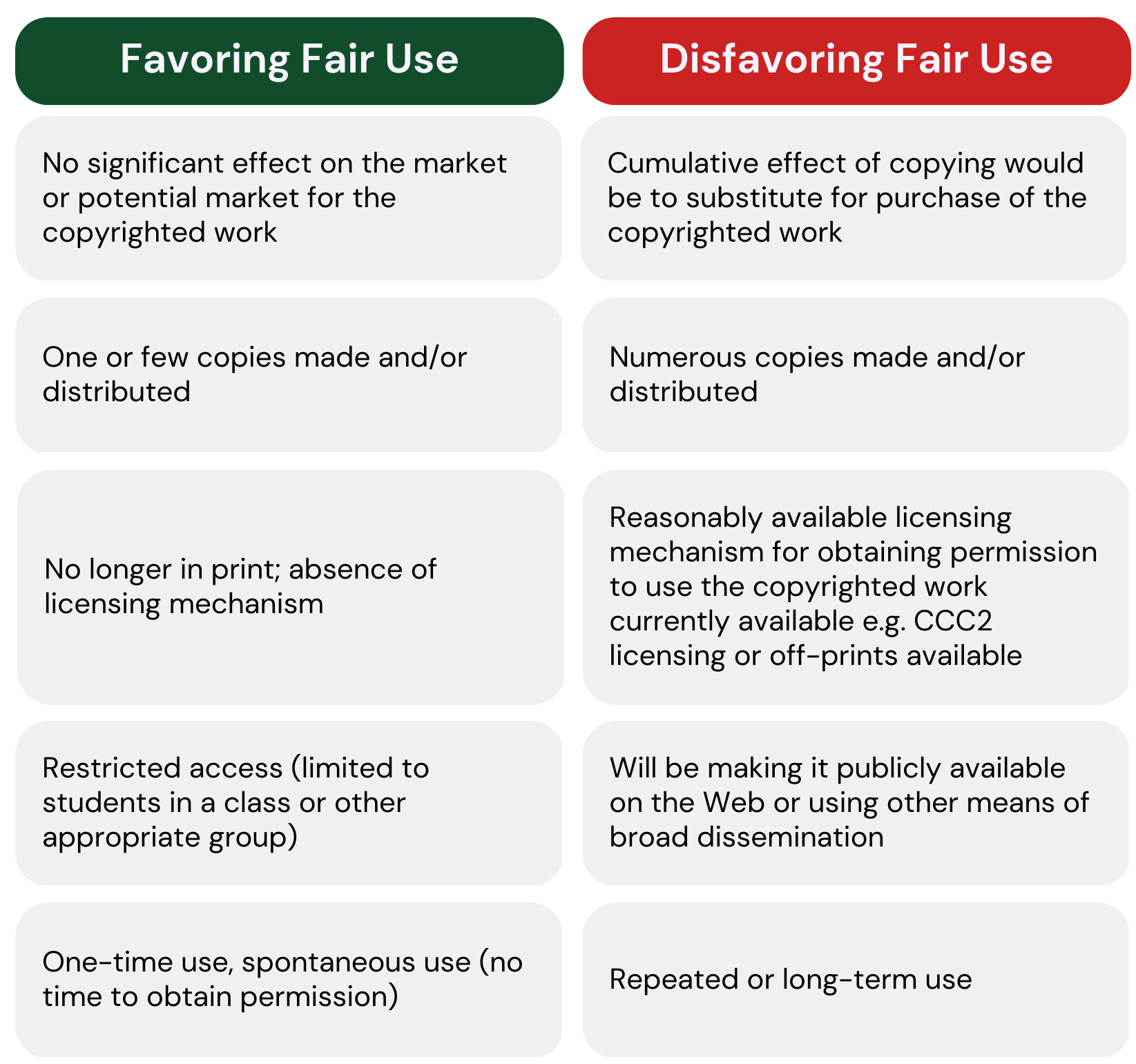

Effect of the Market for Original

What are licenses?

Licenses are permissions given by the copyright holder for their content. Licenses can be applied to copyrighted material in order to give permission for certain uses of the material. Copyright is still held by the creator in these cases, but the creator has decided to allow others to use their work. Sometimes licenses are purchased and sometimes they are given freely by the creator.

Licenses can be applied to allow reuse, redistribution, derivative works, and commercial use.

Creative Commons is the most frequently used and accessible free licensing scheme, but there are others that are used by certain communities. Licenses can also be applied by commercial entities that own copyright to an item such as a journal article. These licenses generally spell out limited usage for users and are available for a fee.

Creative Commons and Open Licenses

Creative Commons licenses are applied by the copyright owner to their own works. These are the most prominently used licenses of their type in the world. There are four components to the licenses that are arranged in six configurations:

- BY - attribution required.

- NC - no commercial use.

- ND - no derivative works.

- SA - Share Alike - the license must be the same on any derivative works.

The ND and SA components cannot be combined, as SA only applies to derivative works.

The six licenses (excluding CC-0 which is an equivalent to the Public Domain) are:

- CC-BY

- CC-BY-SA

- CC-BY-ND

- CC-BY-NC

- CC-BY-NC-SA

- CC-BY-NC-ND

The following chart illustrates the permissions allowed by each license.

- CreativeCommons.org

The Creative Commons website gives more information about the license and has a helpful license generator for your work.

- CC License Compatibility Wizard

This helpful tool can assist you with understanding how multiple CC licenses can work together when re-used in a single work. It is directed towards people creating Open Educational Resources, but can be used by anyone.

- How to give attribution with Creative Commons Licenses

This link shows best practices for attributing Creative Commons licensed content.

(Information for this section pulled from the "Copyright and Intellectual Property Toolkit" from the University of Pittsburgh Libraries.)

What is a Permalink?

Permalinks, also known as stable or persistent links, provide direct access to a specific page or article. These links are designed to last for years and will provide stable access to the resource.

How to find a Permalink

Finding permalinks will vary in each database. If a database provides permalinks it will most likely be with the other limiters or tools in items record.

Finding Permalinks in LibrarySearch

- From the search results list, click on the ellipsis in the right corner. This will open up additional tools including the Permalink option.

- In the expanded tools window, click Permalink. This will display a stable link for sharing.

Why use Permalinks?

Copyright Compliance. When you share a permalink, the receiving users will need to sign in using their Albion College SSO credentials. This means that the user is accessing the article themself, which is the preferred method of sharing. Downloading and sharing PDFs is not copyright compliant.

Library Statistics Matter. We track usage statistics of resources in order to evaluate their impact on campus.

Example: If a professor downloads a PDF of an article and prints copies or emails the PDF to their class of 20 students we will only see that one individual accessed the database. But if the article is shared as a Permalink, the Library will see that 21 individuals accessed the database.

U.S. Copyright Office

U.S. Copyright Office

The Copyright Office is responsible for administering a complex and dynamic set of laws, which include registration, and the recordation of title and licenses.

Copyright Law of the United States of America

U.S. government's copyright law at copyright.gov.

Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, Third Edition

Released by the Register of Copyrights, representing administrative practices of the U.S. Copyright Office.

Other Resources

Association of Research Libraries

Copyright and IP focus page: contains information on fair use and legislation as it applies to libraries, as well as author rights. Contains a code of best practices for fair use by libraries.

Creative Commons

Creative Commons is a nonprofit organization that helps overcome legal obstacles to the sharing of knowledge and creativity to address the world’s most pressing challenges.

Copyright Clearnace Center

CCC helps organizations integrate, access, and share information through licensing, content, software, and professional services